Alice Boughton

Alice Boughton (1866-1943)

Just over two years ago I attended a workshop on Photogravure - I have a project in mind for it. It was quite difficult to say the least. Go further back and I attended yet another workshop - this time to learn the Bromoil process - this was a disaster! However, the workshop itself was fun and the tutor was extremely knowledgeable. We started from scratch - making up the chemistry and working in the darkroom one day; on the second day we sat down with our inks and brushes and prepared to create beautiful pieces like the Pictorialists. Only this didn’t happen! Instead we just ended up with a sludgy mess or images that refused to be inked. I don’t think I have laughed so much on a photography course.

When you leave a workshop, you usually leave like a child leaving a birthday party - walking to your car or train with a big smile on your face carrying your goodies (prints). Not this time! However, I can honestly say that I learned so much on that course and managed to make prints when I got home - still with an enormous amount of failure of course.

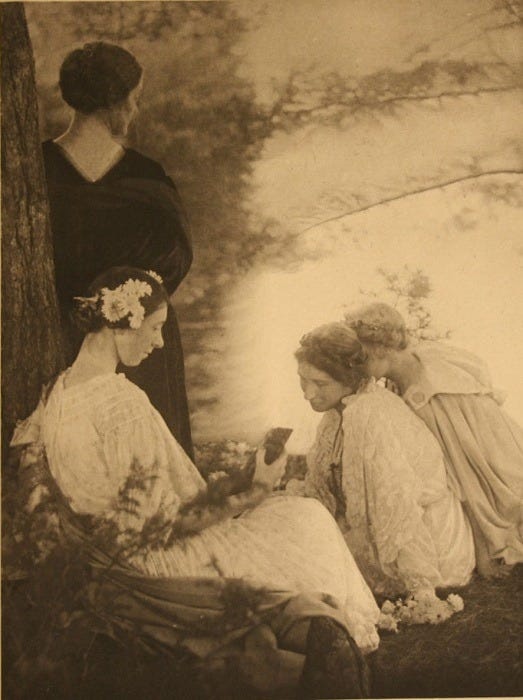

So, when I look at the work of photographers such as Alice Boughton, I am in awe of their skill, patience and artistry. I am also surprised that her name is rarely discussed in photo history and other than one published book on famous people that she photographed (long out of print) - there is nothing else published. You will find a lot of her work on the likes of Pinterest - usually uncredited - or online galleries printing her work so we can hang them in our bedrooms. But biographical details or published monographs of her work are scant or non-existent.

I first came across the work of Alice Boughton through my interest in the Pictorialists and in particular the Photo-Sucession group established by the photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Pictorialism is often regarded as sentimental and this is often a criticism rather than a positive feature. However, as a person who views with my heart and not just my head, this is work that I find engaging and has influenced my work in some form or another. When I look at such beautiful images, I am transported - I may not always question them for a deeper meaning but I am captivated by them. And let’s face it - with the world in such a mess, we need beauty and we need crafts(wo)manship and vision.

Back to Alice Boughton then. Alice Boughton was born 14th May, either in 1865 or 1866 (depends on what source you read) in Brooklyn, New York to Frances Ayres and William H.Boughton who was a lawyer. In the 1880’s she attended the Pratt Institute in New York to study painting and photography. The Pratt Institute was seen as a progressive college, founded in 1887 by the wealthy industrialist and philanthropist Charles Pratt. The institute, according to their website, embraced a philosophy of affordable education for all regardless of class, color or gender.1

Whilst at the Pratt Institute, Alice met two women who would shape both her professional and personal life. The painter Ida C. Haskell (April 1861-Sept 1932) was Alice’s teacher at Pratt and the two of them formed a lifelong relationship - eventually moving in together until Haskell died in 1932. Haskell also accompanied Boughton on a trip to Europe in 1926.

The other important woman was the photographer Gertrude Käsebier (1852-1934) who was a fellow student at Pratt. On leaving the Pratt Institute, Alice and Gertrude went to study in Europe - both had developed a passion for photography and, in particular, photography as art. It is said that Käsebier set up a summer studio in Paris and Boughton was her assistant. Boughton was also Käsebier’s assistant at her studio in New York.

The Photo-Secession Group.

The Photo-Sucession was a group formed by the photographer Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) whose mission was to promote photography as fine art. In 1902, Stieglitz invited Boughton (as well as Käsebier) to show their work at the ‘Little Gallery of the Photo-Sucession’ inaugural exhibition. In 1906 she was elected to the Photo-Sucession group and would have some of her work published in Steiglitz’ influential journal ‘Camera Work’.

Although Stieglitz invited women into the Photo-Sucession group, many of them, with the exception of Käsebier, have been overlooked in the history of photography. Indeed, Boughton is one such woman as are; Eva Watson-Schütze, Sarah C.Sears and Mary Devenbut. As Naomi Rosenblum writes that over the years, Stieglitz’s support for women photographers and for Pictorialism became steadily less forceful.2

When researching Alice Boughton, I really wanted to find something in which I could hear her voice and know her opinions. The only thing I could find was an essay that had been published in Camera Work. However, when I looked through my book ‘Camera Work’, The Complete Illustrations. 1903-1917’ published by Taschen, I could not find it. I found her images but not her essay despite it having multiple essays published by men.

I eventually found it online and it is a really interesting piece called Photography, A Medium of Expression. The first thing that struck me was the fact that the Editorial team distances itself from what she has written. They write: This article in parts conflicts with some of our own views on photography.3 Why? I believe it is because she does not argue that photography has to sit alongside fine art and that we should not disguise the fact that it is a photograph and pretend it is something else. She embraces all the mechanics of a camera and the various printing processes that allow the photographer to make beautiful works of art that stand on their own as photos and do not pretend to be paintings. She doesn’t believe that we should hide the fact that an image is made with a camera and she railed against those who mimicked artists such as Rembrandt or Whistler. She writes:

To have their productions not in the least resemble a photograph, seems to be the goal of some of the new workers, but this attitude is both forced and false. Why not avowedly use the camera? Why be ashamed, because it is not something else?4

Boughton goes on to talk about the different processes that are used to create her beautiful and evocative images - such as the Gum Bichromate process. Having never made prints with this method, I am afraid that I can’t give a personal account. However, as with all these historical processes, there is a level of skill and patience needed. I once wrote of the many plates that Julia Margaret Cameron went through to get one that she was happy with and I can imagine that this would be the same with Boughton and whatever processes she deemed necessary to fit her vision.

Reading her essay and her obvious passion for her craft was enlightening. She talks about the many uses that photography has - such as creating artist portraits, or documenting buildings. The arguments that she was having then, Julia Margaret Cameron was having before her, and with the advent of the digital camera and smartphones, these arguments surrounding photography abound. However, I can’t help feeling that Alice and I would agree that we are just lucky to be in a position in which we have so many tools at our fingertips to create art with or just have fun with.

Studio Portraits.

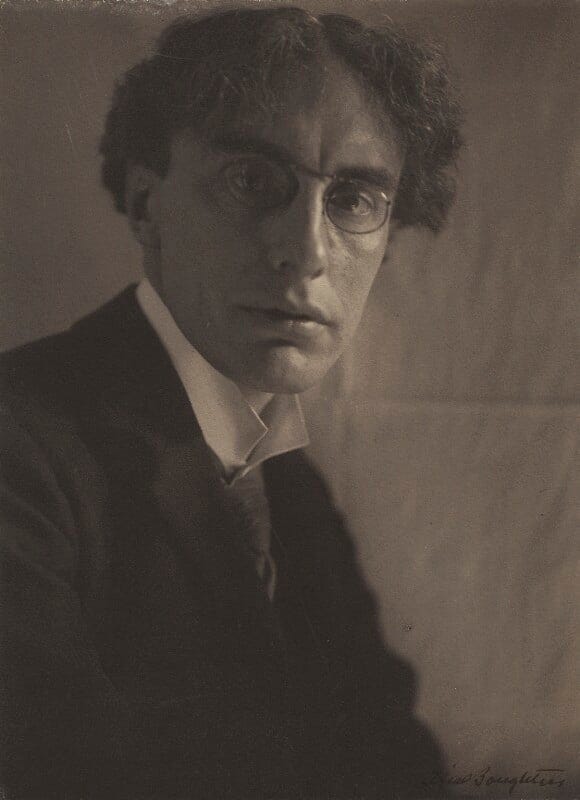

As we can see, Alice Boughton was an independent woman, with an independent mind and eventually became an independent photographer. After working for Käsebier, she set up her own studio in New York in 1890, where she would gain a reputation for her portraiture that would attract those in the literary and art world - these included W.B Yeats, Roger Fry, Robert Louis Stevenson and Henry James. A letter addressed to Yeats suggests that at some point she may have had a second studio as the headed paper was a different address to that of her first studio. In 1915 she hired Margaret Watkins (1884-1969) as an assistant. Watkins would go on to be a trailblazer in Modernist Photography, thus rejecting Pictorialism.

In 1931, after 40 years, Alice Boughton closed down her New York studio and destroyed over 1000 prints. She moved to Long Island and lived with her partner Ida C. Haskell. Boughton died from pneumonia on 21st July 1943. She leaves behind an incredible photographic legacy in which her work is held in archives around the world, including the National Portrait Gallery, London and the George Eastman Museum.

Pratt Institute website: Pratt.edu

Noami Rosenblum, The History of Women Photographers, p.107. AbbeVille Press

Camera Work, edition 26

Camera Work, edition 26

That was a great read. I like to think similar about the folks of old, that they'd encourage us to make use of the tools at our disposal within ethical usage.

Such an intriguing story. The anti-Pictorial Pictorialist? I’m sure there will be plenty of contemporary photographers who future historians will rediscover. Do we know why she destroyed her images and abandoned photography?